Anita’s Blog – Gardening For Bats

- jjvanm

- Nov 11, 2025

- 7 min read

If you haven’t heard, November through February is tree planting time in the Rio Grande Valley.

We are entering that cooler time of year when it’s kinder to plant trees and shrubs while they are dormant. They will establish over the winter, without the heat stress of summer, and then begin flourishing in spring.

As Texas Master Naturalists, we promote native plants, of course, and I like to include a bit of background whenever I give presentations to civic groups. I tell them that in order to be a native plant it has to have survived hundreds of years in the Valley’s diverse and sometimes harsh and extreme environment of:

· drought,

· floods,

· heat,

· freeze,

· sun,

· wind,

· salt,

· snow

-- and sometimes all in the same year.

“Gardening for Bats” is the title of one of my presentations that gets a number of requests.

The first portion of the presentation talks about eight possibly annoying plants that are probably in everyone’s yard and generally considered weeds. The second part is about something I wasn’t expecting when I began experimenting with attracting moths with a black light and moth sheet. Very quickly, audiences grasp the synergy of these two divergent pursuits.

In my presentation, I include the value those annoying plant species provide to native wildlife, which is recapped briefly below:

Ruellia, Ruellia nudiflora, prolific. Nectar for butterflies; leaves are eaten by white-tailed deer; bobwhite quail eat the seeds; larval host for six butterflies: common buckeye, pale-banded crescent, malachite, white peacock, banded peacock and Texan crescent butterflies.

Mexican hat, Ratibida columnifera, hearty re-seeder. Nectar for bees, butterflies, other nectar insects; ripe seeds eaten by seed-eating birds, songbirds, small mammals and Rio Grande turkeys. Nice, full, bushy stature -- hold that thought for later.

Berlandier’s trumpets, Acleisanthes longiflora, come up along the edges of sidewalks and driveways; good nectar; larval host plant for white-lined Sphinx moths.

Golden Wave, Coreopsis tinctoria, nice, dense, bushy habitat; nectar for butterflies and bees; finches and sparrows eat the seeds.

Pepperweed, Lepidium austrinum, a short but full shrub-like plant pollinated by a variety of insects and bees. Nectar and seeds are food sources; host plant for some of the white butterflies, like checkered white and possibly cabbage and great Southern white butterflies.

Redseeded plantain, Plantago rhodosperma, of “Walker, Texas Ranger” fame (anti-inflammatory poultice out on the range). It is used to revegetate wildlife habitats and rangelands for forage; foliage is eaten by Rio Grande turkeys, white-tailed deer, cattle, Texas tortoise, scaled and bobwhite quail and mourning doves. As a conservation plant, it has been used in erosion control along streams in its range.

Common purslane, Portulaca oleracea, native succulent; ancient worldwide distribution; flowers attract pollinators, flies, small bees, and beetles. Rodents, like squirrels, rats and mice eat the flowers. Sparrows, and other birds, eat the seeds. Herbivores eat the leaves. It is a larval plant to purslane blotchmine sawfly, purslane moth, white-lined sphinx and other caterpillars.

Three-lobed false mallow, Malvastrum coromandelianum, like a miniature buttercup; not native. Larval host for common and tropical checkered-skipper, red-crescent and scrub-hairstreak butterflies. The leaves are possibly eaten by rabbits and Texas tortoises.

In addition to plants benefitting wildlife, there are other aspects of our gardens we should know about before we arbitrarily think we should get rid of something, especially if we don’t know what it is, be it plant, bug or critter.

Jumping abruptly: Mothing is the art of attracting moths at night. It is a fascinating – if not somewhat addicting – pastime. My setup is simple: three black light bulbs screwed into shop lamps clamped to my old tripod and a white sheet stretched over a frame made of two by fours.

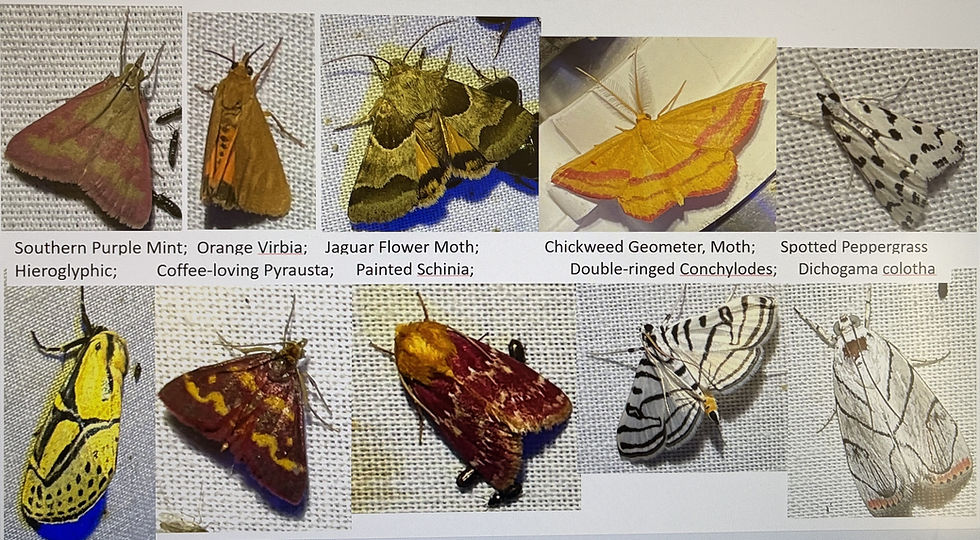

Unexpectedly, I not only attracted moths, I attracted things I’d never ever even imagined. It was frightening and fascinating all at the same time! Scads of lovely bugs with clever names flew to the black light.

I've photographed hundreds of species of beautiful and interesting moths and other, sometimes frightening, nighttime fliers in all sizes, shades and colors that have visited the moth sheet and been identified via iNaturalist.org over the past five years.

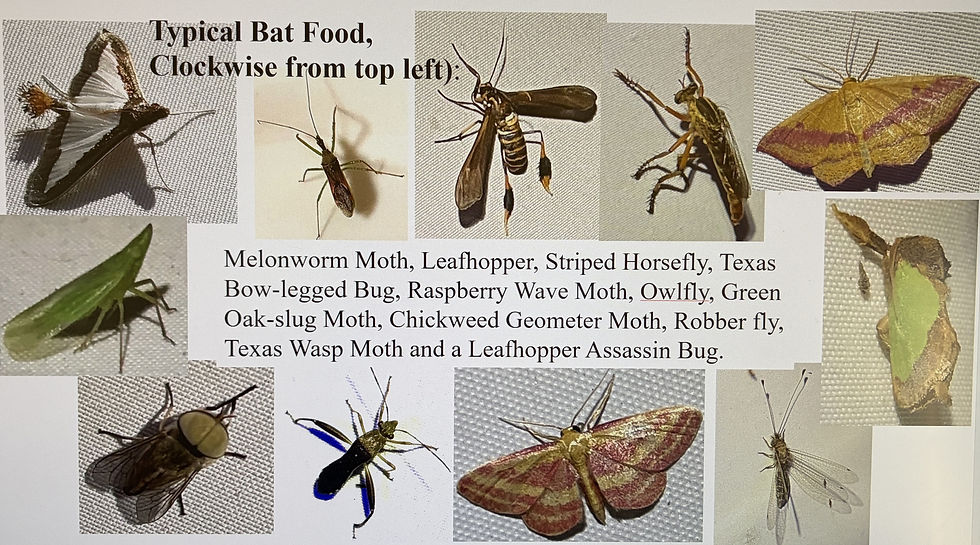

Here’s how all this buggy information fits in with the annoying garden plants to become a story about gardening for bats. Many of you know that bats eat mosquitoes. They also eat a whole lot of other things. Gardening for bats is really gardening to attract insects, specifically, night-flying insects.

A good number of bats are nectivorous, but our Rio Grande Valley bats aren’t. Most of them are insectivores.

Native plants attract native bugs – daytime bugs and nighttime bugs. Insectivorous bats eat night-flying bugs. If we provide plants that attract bugs, we’re helping the bats and the habitat all around.

Bats are important beneficial mammals. Texas has more bat species than any other state: 33 of the 43 species found in the United States.

Below are the diets of some of the bats active in the Rio Grande Valley:

Southern yellow, Lasiurus ega, is typically on our Southern Texas Plains and Gulf Coastal Plain, possibly remains year-round. Their diet is small- to medium-sized flying insects.

Northern yellow, Lasiurus intermedius, a solitary bat, prefers roosting in trees near permanent water in Spanish moss, like at Santa Ana nature preserve, or in palm trees. At dusk, they can be seen feeding around streetlamps and over open areas, like golf courses. They are non-migratory but may go into torpor during extreme winter weather.

Evening bat, Nycticeius humeralis, catches insects midair during slow, steady flights at dawn and dusk. Their diet, beetles, moths, flies, June bugs, spittle bugs, stink bugs, flying ants,

Hoary bats, Lasiurus cinereus, also solitary, hunt for prey while flying over wide-open areas or lakes, feeding on moths, beetles, flies, crickets and true bugs.

Silver-haired, Lasionycteris noctivagans, bats have a most diverse diet. They hunt for soft-bodied insects, like moths and spiders by foraging low to the ground, unlike many other bats. They also eat flies, midges, leafhoppers, moths, mosquitoes, beetles, crane flies, lacewings, caddisflies, ants, crickets and agricultural pests.

Mexican free-tailed bats, also known as Brazilian free-tailed bats, are the most common throughout Texas and in the Valley. In most of the state, they are migratory and spend winters in caves in Mexico. Where the climate is mild and food is available, bats may not migrate nor hibernate. Mexican free-tailed bats are aerial insectivores; they consume moths, beetles, flies, cicadas, assassin bugs, hoppers, ants, wasps and other night-flying prey while they, too, are on the wing.

Eastern Red Bat, Lasiurus borealis, found throughout the state mostly eat larger prey, like moths and beetles, and also planthoppers, leafhoppers, spittlebugs and ants.

Bats live in hollow trees, tree cavities, crevices under bridges – caves in certain parts of the state.

Bats are especially fond of palm trees when the palm skirt is allowed to remain.

Loss of habitat affects every aspect of native wildlife. Bats especially suffer from the loss of palm tree skirts. Those dead-looking palm branches house hundreds of bats.

Gardening to attract insects ultimately attracts bats. With our cooler months approaching, it’s a good time to plant.

You may already be providing food and lodging for insects and bats if your neighborhood has palm trees with skirts, Texas ebony, anacua, hackberry, mesquite, Mexican olive trees and dense shrubbery.

During the day, night-flying insects seek out shelter to hide and rest.

Don't do a massive after-summer-garden-clean up.

Insects also hide out in vegetative debris that collects under plants. Small piles of sticks and leaves under shrubs also make good cover for insects. Downed tree branches, if you have the means to cut them to size, can be tucked under large shrubs and left to decay, making good breeding grounds for insects all year. Many insects are looking for shelter in which to spend the winter.

Although the approaching winter months are not the time to attract moths, other insects and bats, it is the right time to prepare to attract and shelter them in the future by planting trees, if you have the room, and dense shrubs. Annual plants are best planted in early spring.

Some suggestions for winter planting:

Turk’s cap, Malvaviscus drummondii, sees a lot of activity. It blooms through much of the winter months and is a hummingbird magnet. It provides food for caterpillars, nectar for butterflies and is a host plant for the rare-to-the-Valley beautiful Art Deco-ish-looking Eusceptis flavifrimbriata moth as well as other butterflies and insects.

Yellow sophora, Sophora tomentosa, is a 3-to-6-foot-tall perennial shrub with arching branches and long-blooming yellow flowers. It can survive temperatures to 20 degrees Fahrenheit; it will come back if frozen to the ground. Nectar for bees and butterflies during the day and moths and nectar-insects at night.

Berlandier’s Fiddlewood, Citharexylum berlandieri, can get to 15 feet tall, branching branches produce tiny white flowers at branch tips which turn into glossy orange and umber colors of berries that turn black when ripe; can bloom and berry all year, inviting songbirds, raucous chachalacas and green jays to its fruit and sheltering branches. The flowers attract butterflies and bees.

A few other plants, vines and shrubs to consider that will shelter bugs.

Thank you for reading this far!